According to the Mahayana (Middle Way) Buddhist tradition, Prince Siddhartha Gautama (563-483 BCE) arrived at Bodh Gaya in the eastern Indian state of Bihar and vowed to meditate under a fig tree (ficus religiosa) until he had achieved enlightenment. It is believed that Siddhartha sat in meditation for forty-nine days, wrestling with the demons of body and mind. When he at last stood up, it was as the Buddha (The Awakened One). The sacred fig under which he sat has been known ever since as the Bodhi Tree (The Tree of Awakening).

Siddhartha was born at the foot of the Himalayas in Lumbini, in what is now southern Nepal. He was raised in the Edenic luxury and seclusion of a palace, separated from the harsh realities of life. Then at the age of 29, he convinced a charioteer to take him on a series of trips out beyond the palace walls. On these excursions he observed first an old man, then a sick man and finally a corpse. He also saw a simple, wandering monk. The charioteer explained to Siddhartha that the monk had given up the ways of the world in order to overcome its sorrows.

Siddhartha was anguished by what he had seen. He resolved to live the life of a mendicant in order to vanquish his own suffering and that of all other sentient beings. Soon after, he exchanged his princely robes for those of a beggar. He left his wife and small son and set out on a pilgrimage that led him to study with several masters over the course of six years. But asceticism brought Siddhartha no closer to his aim and he found himself at Bodh Gaya, seeking a middle path between self-mortification and hedonisim. There beneath the fig tree, he lowered himself to the ground, determined not to rise again until he had awakened from the woes of this life.

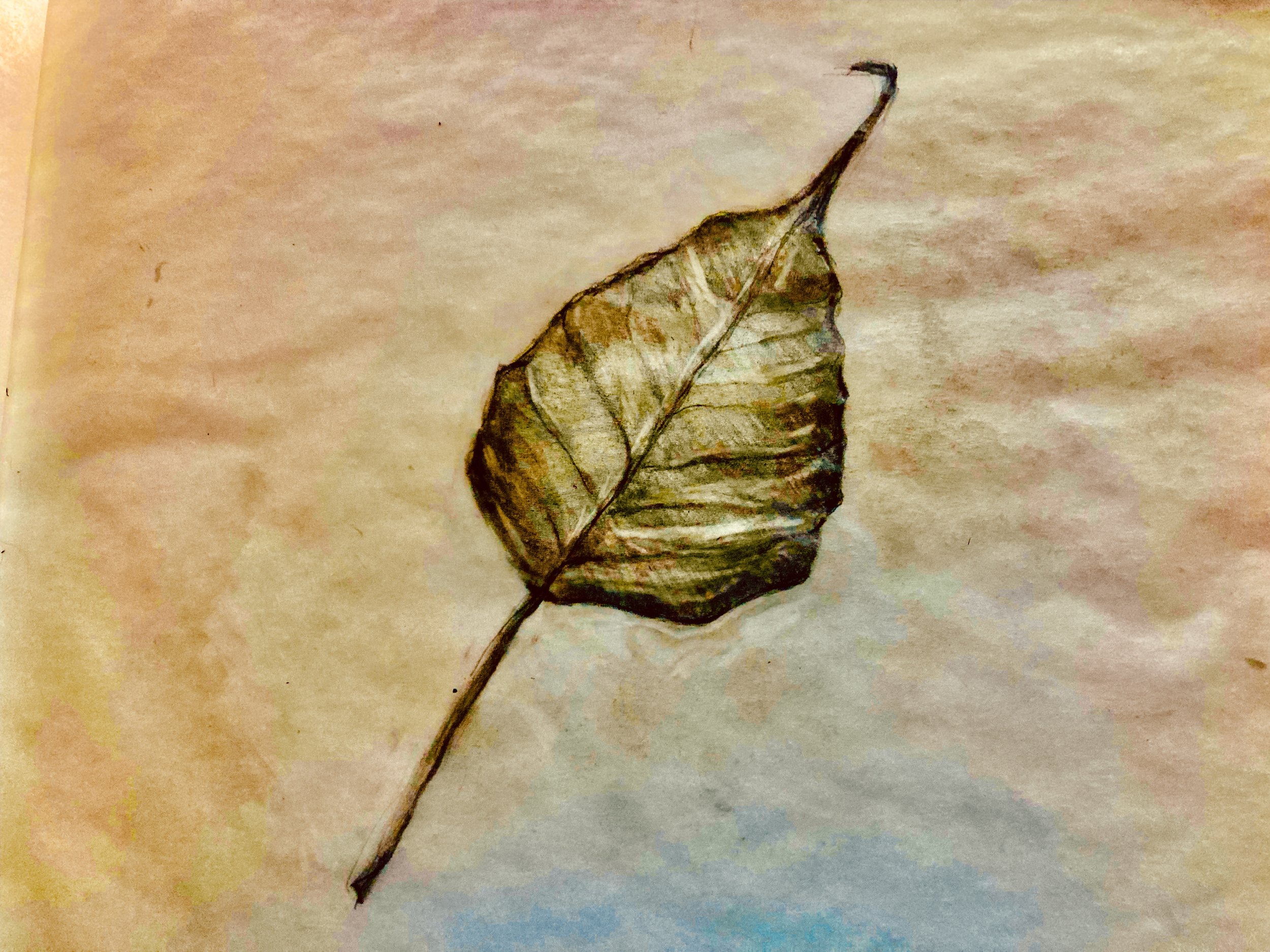

Last Saturday, I threw disinterested glances at the numerous stacks of unfinished miscellania that lay about the house. Projects, papers and clutter spilled out all around and beckoned to me from every corner, but I closed my eyes and ears to them. I pulled out a sketchbook instead. I found the plain white envelope that my dear friend had presented to me when she returned from a trip to Sri Lanka just over two years ago. Inside the envelope was a leaf from a tree that grows in Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka and is believed to be a descendant of the Bodhi under which Siddhartha sat at Bodh Gaya.

I communed with my pencil and paper and the leaf all day. To draw something in detail is a meditation in itself. The first things I noticed about the leaf were its heart shape and the gentle undulation of its surface. The next was the intricate pattern of veins that ran from its central channel to its prickly edges. These were what I wanted to express in the drawing. However, a sensitive drawing reveals something beyond the contours and the specifics, something midway between objectivity and subjectivity. I knew the leaf had more to say.

Every leaf is a testament to the miracle of photosynthesis. Each of a tree’s leaves unfurls, like so many hands, accepting all that pours down from the heavens and all that seeps up from the earth. If we could turn our palms up to the sun and breathe like that, if we could freely give and receive the dichotomies of this world, we, too would turn air and light and water into food.

I spent several tranquil hours drawing. By the time the clear afternoon light had begun to shift toward the golden rays of evening, something new had emerged from my sketchbook’s page. From the treetops, the familiar triptych screech of a red-tailed hawk pierced the silence. I looked up and imagined the raptor peering down as if from the roof of the world, witnessing in each of us a Siddhartha, seated beneath a universal canopy of leaves, listening for the infinite echo of just one leaf clapping.